10. PARTICIPATION

For both adults and children the development of such a culture of participation can be a very powerful exercise in democracy.

Participation is both an essential principle of human rights and a working practise of citizenship for all people. The affirmation of the right of children to participate is one of the guiding principles and most progressive innovations of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (See Chapter I, p. 21 for a discussion of the Children’s Convention).

The Children’s Convention articulates several different aspects of children’s right to participate:

- the right to express their views on all matters affecting them and to have their views given due weight (Article 12)

- freedom of expression, including the right to seek and receive impartial information of all kind (Article 13)

- freedom of thought, conscience and religion (Article 14)

- freedom of association (Article 15)

- the right of access to information and material from national and international sources (Article 17)

- the right to participate in the cultural life of the community (Article 31).

Why is children’s participation important?

The most important precondition of meaningful participation is that adults respect children’s capacities to take part in decisions and recognise them as partners. Rather than traditional relationships built on adults’ power and control over children, democratic partnerships result. Otherwise children’s participation is merely tokenism: children may give their opinions, but they have no influence on whether or how their contribution is used.

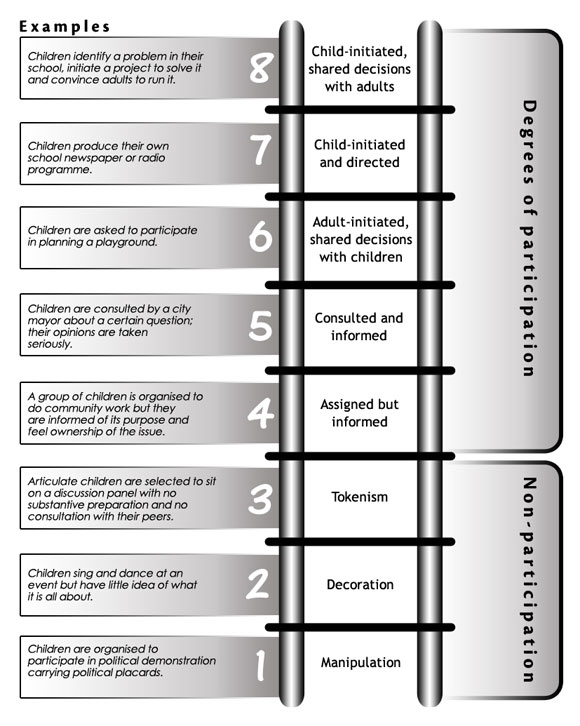

The essence of participation was well explained by the ‘Ladder of participation’ model1. Roger Hart describes an eight-stage Ladder of Participation. The first three stages are manipulation, decoration and tokenism, false means of participation that can compromise the entire process. Real forms of participation include the ‘Assigned and informed’ stage in which specific roles are given to children, and the ‘Consultation and informed’ stage in which children give advice on programmes run by adults and they understand how their opinion will affect the outcome. The most advanced stages are ‘Adult initiated’ participation, a shared decision making process with children, and ‘Child-initiated and directed’ projects in which adults appear only in a supportive, advisory role. This last stage provides children with the opportunity for joint decision making, co-management and shared responsibility with children and adults accessing each other’s information and learning from each other’s life experience.

Successful participation is not limited to a single project but is an ongoing process that contributes to building a culture of participation throughout a child’s environment: in the family, in the school, in caring institutions, in the healthcare system, in the community and in society. For both adults and children the development of such a culture of participation can be a very powerful exercise in democracy. The resulting understanding of human rights and the encouragement of active citizenship benefit the whole of society.

How to exercise participation with children

First and foremost children’s participation needs an enabling environment. Children open up when they feel what they say has significance and when they understand the purpose of their involvement.

Because children think and express themselves differently from adults, their participative processes should build on concrete issues and experiences and real life situations, and vary in complexity based on the evolving capacity of the child. Starting exercises might be consultations and opinion surveys on various subjects directed by adults. Planning, implementing, managing, monitoring and evaluating programmes are a more developed means of participation. Child-initiated projects, research, self-advocacy, representation or co-management with adults of organisations and institutions are highly educative and strong experiences for older children.

QUESTION: Who decides what kind of participation is appropriate for children at different levels of maturity? How is such a decision made?

Meaningful participation processes develop a wide range of skills and competencies. Children gain new information, learn about their rights and get to know others’ points of view by active listening. Forming and articulating their opinion, they improve their communication, critical thinking and organisational and life skills. They experience that they can make a real difference.

To achieve the culture of human rights in Europe, the implementation of children’s participation is an ongoing mission. Its biggest barrier is engrained adult attitudes. Therefore, capacity building for both children and adults on human rights, children’s rights, facilitation, ethical practises, and research is necessary. All people working with and for children should internalise the basic principles of children’s participation and develop capacities to facilitate, support and promote it. Political and personal commitment is essential. Although building a culture of participation requires human and financial resources, the results validate the effort.

Examples of good practise

Good examples of successful children’s participation can be seen all over Europe.

Family: Children’s participation can begin at home with very young children playing a role in family decision making. Child participants of the Council of Europe’s conference on ‘Building a Europe with and for Children’ reported:

We have successfully participated in making decisions with our families about ... how we would like to spend our free time, choosing what we want to eat, sometimes even choosing which school ... to attend, how we split tasks in the family, resolving family problems, organizing family events.2

School: Schools can be important models of good participation. Producing school rules together or entrusting children with decoration and keeping order in their classroom can be good starting points that also help children identify with their school environment. However, school councils and children’s parliaments are only valid exercises in participation if they are given real decisions to make. Children can also participate in addressing school problems such as bullying, exclusion or other forms of school violence. Children’s initiatives to produce a newspaper, radio-programme or Internet pages, to organise clubs, festivals or campaigns are also important contributions to democratic school life.3

Leisure activities: Children’s out-of-school programmes can provide children with experiences that show their participation makes a difference. NGOs, informal locations, street programmes, festivals, the Internet and new media platforms offer various opportunities to exercise democracy. Out-of-school activities can often be complementary to school projects.

Vulnerable children: Participation is extremely important and empowering for vulnerable children. Children living in poverty or in institutions often lack even minimal forms of participation. All children should be received into a friendly environment by well-trained staff when they arrive at an institution or hospital or face a police action or a judicial process, either as victims or offenders. Children’s best interests can only be respected if they are asked to express their views and comment on such processes.

Children’s participation in governmental processes

Community level: A wide range of good opportunities exists for children’s participation in projects that improve the well-being of their community. The Council of Europe has produced a Recommendation on the promotion of young people’s participation in municipalities, which can provide a good starting point for action both for municipalities and children’s groups themselves.4

QUESTION: How can we encourage children to participate in government and also protect them from political manipulation by adults?

Several good examples exist of law and policy makers who regularly consult with children. In London, for example, the Lord Mayor consults children about how to make the city more suitable for all young people, especially in areas such as transport, playgrounds, safety, and Internet violence.5 In Scotland, a five-year Community Partners Programme set out to explore how active community participation could be an effective means of countering children and young people’s exclusion. Resulting programmes, methodologies and results have been summarised in a guidebook.6

National level: A few European countries have a national policy to promote children’s participation. For example, in Germany, Norway and Great Britain governments support the effective involvement of children and their families or care-givers in the development and running of all children’s trusts, and encourage municipalities and organisations to do so the same. Because such innovations require changes in organisational culture, moving from commitment to practise often proves difficult.7

International level: Children can participate best in local and national processes where their daily experiences can effectively be taken into consideration. However, in a well-planned context children can also be involved in international decision making processes.

The participation of children and young people has been a central pillar in the process of the UN Study on Violence Against Children. Children were involved in regional consultations and their recommendations were included in the final documents of those consultations. Although the unfamiliar process challenged the organisers, it produced some of the most stimulating and insightful results.8

Principles for promoting children’s participation

UNICEF, the worldwide NGO fighting for children’s rights and well-being, has set up principles to ensure children’s meaningful participation. These guidelines are useful for any form of participation:

- Children must understand what the project or the process is about, what it is for and their role within it.

- Power relations and decision making structures must be transparent.

- Children should be involved from the earliest possible stage of any initiative.

- All children should be treated with equal respect regardless of their age, situation, ethnicity, abilities or other factors.

- Ground rules should be established with all the children at the beginning.

- Participation should be voluntary and children should be allowed to leave at any stage.

- Children are entitled to respect for their views and experience.9

Relevant human rights instruments

Council of Europe

Participation is an important area of the Council of Europe’s work, especially regarding youth. In a unique manner the Council of Europe has introduced a co-management system into its youth sector, where representatives of European youth organisations and governments decide jointly on the Council’s youth programme and budget. In cooperation with the Congress for Local and Regional Authorities, a European Charter on the Participation of Young People in Local and Regional life was produced in 1992 and revised in 2003. This unique tool not only promotes participation of young people, but also presents concrete ideas and instruments that can be used by young people and local authorities. A practical manual with further ideas, ‘Have your say!’, was produced in 2007.

United Nations

The rights related to participation are closely linked to those of citizenship, both in the range of freedoms they confer and the responsibilities they impose. (See discussion of Theme 1, Citizenship, p. 213) The Universal Declaration of Human Rights recognizes in Article 29 the importance of the citizens’ participation to both the community and the citizens themselves:

Everyone has duties to the community in which alone the free and full development of his personality is possible.

However, only with the adoption of the Convention on the Rights of the Child in 1989 were the rights and benefits of participation recognized as applying to children. Their participation is guaranteed in a wide spectrum of the life of the community:

- Article 9: to participate in proceedings regarding the child’s guardianship or custody

- Article 12: to participate in decision making in “all matters affecting the child”

- Article 13: to express opinions and to acquire and give information

- Article 14: to hold views in matters of thought, conscience and religion

- Article 15: to associate with others

- Article 23: the right of a child with disabilities to “active participation in the community”

- Article 30: the right of minority or indigenous children to participate in the community of their own group as well as the larger society

- Article 31: to participate fully in cultural and artistic life.

The Children’s Convention defines a child as anyone below the age of eighteen, which necessarily means not every child has the competence or maturity to participate in the same way. To address this fact, the Convention applies the principle of evolving capacity, recommending that both parents and the state recognize and respond to the child based on his growing abilities and maturity. Many adults and institutions continue to be challenged to adapt their long-established attitudes and practises to accommodate the child’s right to participation at any age.

Useful resources

- Backman, Elisabeth, and Trafford, Bernard, Democratic Governance of Schools: Council of Europe, 2007:

www.coe.int/t/dg4/education/edc/Source/Pdf/Documents/2007_Tool2demgovschools_en.pdf - Brocke Hartmut and Karsten, Andreas, Towards a common culture of cooperation between civil society and local authorities, Centre Francais de Berlin, Berlin, 2007

- Building a Europe for and with Children, Children and young people’s preparation seminar: Council of Europe, Monaco, 2006

www.coe.int/t/transversalprojects/children/Source/reports/MonacoPrepSeminar_en.doc - Catch Them Young, Recommendations on children’s participation, Ministry of Flemish Community Youth and Sport Division, Benelux, Brussels, 2004: www.wvc.vlaanderen.be/jeugdbeleid/internationaal/documenten/catch%20them%20young.pdf

- Children and Young People’s Participation, CRIN Newsletter No 16: Child Rights Information Network, October 2002: www.crin.org/docs/resources/publications/crinvol16e.pdf

- Children, Participation, Projects – How to make it work: Council of Europe, 2004:

www.bernardvanleer.org/files/crc/3.A.5%20Council_of_Europe.pdf - DIY Guide to Improving Your Community – Getting children and young people involved: Save the Children, Scotland, 2005:

www.savethechildren.org.uk/scuk_cache/scuk/cache/cmsattach/4130_DIY.pdf - Dürr, Karlheinz, The School: A democratic learning community, DGIV/EDU/CIT (2003) 23final: Council of Europe, 2004: www.coe.int/t/dg4/education/edc/Source/Pdf/Documents/2003_23_All-EuropStudyChildrenParticipation_En.PDF

- Gozdik-Ormel, Zaneta, ‘Have your say!’ Manual on the Revised European Charter on the Participation of Young People in Local and Regional Life: Council of Europe, 2007.

- Hart, Roger, Ladder of Participation, Children’s Participation: From Tokenism to Citizenship: UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre, 1992.

- Learning to Listen, Core Principles for the Involvement of Children and Young People: Department of Education and Skills, Children’s and Young People’s Unit, UK, 2001:

www.dfes.gov.uk/listeningtolearn/downloads/LearningtoListen-CorePrinciples.pdf - Promoting Children’s Participation in Democratic Decision making: UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre, Florence, 2001: www.asylumsupport.info/publications/unicef/democratic.pdf

- Recommendation No. R(81)18 of the Committee of Ministers to Member States concerning Participation at Municipal Level, Council of Europe, 1981:

http://wcd.coe.int/com.instranet.InstraServlet?Command=com.instranet.CmdBlobGet&DocId=673582 &SecMode=1&Admin=0&Usage=4&InstranetImage=45568 - Seven Good Reasons for Building a Europe with and for Children: Council of Europe, 2006: www.coe.int/t/transversalprojects/children/publications/Default_en.asp

- Sutton, Faye, The School Council – A Children’s Guide, Save the Children, 1999.

- The United Nations Secretary General’s Study on Violence against Children: www.violencestudy.org

Useful Websites

- L’Association Themis: www.grainedecitoyen.fr

- Child Rights Information Network: www.crin.org

- Children as Partners Alliance (CAPA): www.crin.org/childrenaspartners

- Children’s Rights Alliance for England (CRAE): www.crae.org.uk

- Frequently Asked Questions on Children’s Participation:

www.everychildmatters.gov.uk/participation/faq - Save the Children: www.savethechildren.net

- UNICEF: www.unicef.org

References

1 Originally developed by Arnstein, Sherry R.: A Ladder of Citizens Participation, JAIP, Vol 35, No.4, 1969, p. 216-224.

http://lithgow-schmidt.dk/sherry-arnstein/ladder-of-citizen-participation.html The model was developed by Hart, Roger: Children’s Participation from Tokenism to Citizenship: UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre, 1992, Florence.

2 Building a Europe for and with Children, Children and young people’s preparation seminar, Council of Europe, Monaco 2006, p.16.

3 Dürr, Karlheinz, The School: A democratic learning Programme Education for Democratic Citizenship DGIV/EDU/CIT (2003) 23final, Council of Europe, 2004.

4 Recommendation No. R(81)18 of the Committee of Ministers to Member States concerning Participation at Municipal Level, Council of Europe, 1981.

5 See Young London Kids: www.london.gov.uk/young-london/kids/have-your-say/index.jsp

6 DIY Guide to improving your community – Getting children and young people involved, Save the Children, Scotland, 2005.

7 Learning to Listen, Core Principles for the Involvement of Children and Young People, Department of Education and Skills, CYPU, UK, March 2001.

8 See The United Nations Secretary General’s Study on Violence against Children.

9 Promoting Children’s Participation in Democratic Decision making: UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre, 2001.